One in four women and one in six men will experience intimate partner violence in their lifetime, and that abuse includes much more than physical violence. Technology abuse is a large and growing problem. The Safety Net Project at the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) focuses on this issue: the intersection of technology and abuse. Although most technology is developed under the guise of improving and bettering our lives, abusive individuals are embracing all opportunities and using technologies in their tactics of abuse. One of the most frustrating things we encounter in our work is when we hear that survivors of domestic violence, sexual violence, and stalking aren’t taken seriously when they expose the tech-facilitated abuse to the very people they reached out to for help. Instead, they are brushed off for being too sensitive, or told that what happens online doesn’t cause actual harm offline. Even worse: That the abuse is somehow their fault.

Below are three stories, each modified to protect the privacy of victims. All are instances of intimate partner technology violence and abuse outlined from the lived experiences of survivors. We offer them up as a rallying cry to public interest technologists who can help these victims overcome the challenges — and their abusers — by creating technological solutions, policies, and practices that address technological abuses.

1) Technological Stalking

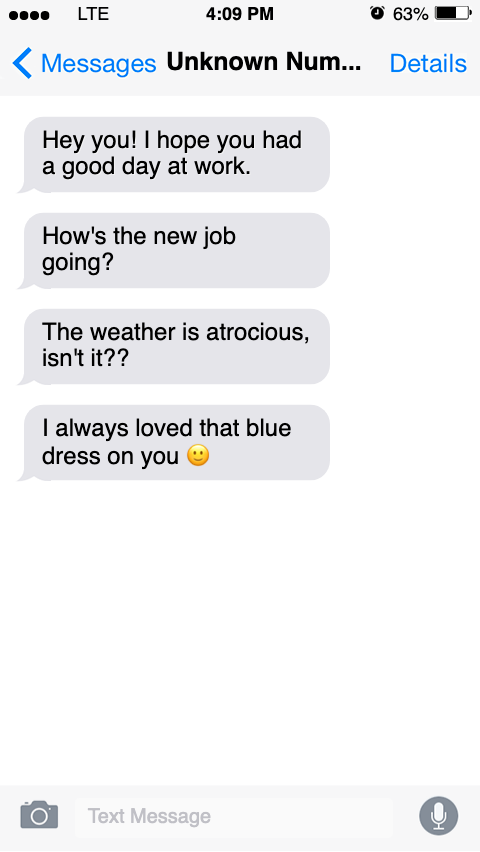

Jen*, whose partner had viciously abused her, got help from a local domestic violence shelter in her community. The organization gave her temporary refuge, helped her relocate to a new state, and replaced her phone and phone number. She got a job in her new town, and was starting to feel a sense of freedom. A sense that maybe, just maybe, she would be able to sleep at night. At the end of her first day at her new job there was a huge thunderstorm. She made a run to her car. Once settled into the driver’s seat, she received a string of text messages from an unknown number:

She knew it was her former abuser. She had no idea how she’d been found, or where her ex was messaging her from. When she reached out to the police for help, an officer looked at the messages, and was confused about why she was so scared. The officer told her she wished her partner would send texts like the ones she received. Jen showed the officer the order of protection, but she was told there was no way to prove who sent the messages. They could be from anyone, and there weren’t any identifiable threats within the messages. Jen’s story is far from rare, as the New York Times detailed several years ago. One research study published in the Journal of Family Violence found that 60 to 63 percent of female respondents reported experiencing technology-based abuse by an intimate partner.

2) Using Technology to Control

Steve* was kept prisoner in his own house through smart home technology. His partner used Internet of Things-based technology in the house to control him. He monitored him using security cameras located inside and outside of the home, and forced him to do a series of demeaning tasks when returning home before remotely unlocking the doors to let him in. While his partner was traveling on business, he was expected to immediately respond to all his partner’s calls or messages, or he’d blast music, turn the lights on and off, and shut off the heat mid-winter to wear him down. When he went to law enforcement for help, they dismissed his concerns as if he was paranoid or imagining things, saying they’d be happy to refer him to a mental health program. Steve is one of many facing the emerging misuse of smart home technology. This report by the New York Times details how as Internet of Things based technology becomes more commonplace, so does the misuse of it by abusers.

3) Online Impersonation Keeps a Victim Unemployed

Stephanie* broke free from an abusive relationship, went back to school, and earned a teaching degree while parenting her two small children. She was in the final stages of the hiring process at a school when, during the background and reference check process, she got a call from one of the administrators. They’d run a search of her name on Google and discovered numerous social media posts with her name and very lewd information. They told her they’d be putting her hiring on hold and wouldn’t be able to bring her on if the posts didn’t come down immediately. She wasn’t aware the posts existed until the administrators called. When she ran a search, she found the same results on the personal page of someone she’d been on a date with a few years prior. She contacted the social media companies and flagged the posts to be taken down. However, they were crafted in a way that didn’t violate any community standards so the companies refused her requests. The posts didn’t come down, and the school withdrew the job offer.

Each of these stories are examples — three of countless others — that demonstrate how intimate partner abuse plays out, and offers a glimpse at the context and impact of the tech abuse tactic victims experience. Survivors tell us they feel haunted, and that they don’t have control over their lives. They tell us that when they finally gather up enough courage to ask for help people don’t believe them because what’s happening doesn’t seem possible. Their experiences of tech abuse are often minimized, victimizing them yet again.

Virtual World, Real Pain

There’s a common misperception that harassment and threats that occur in an online or mobile space don’t have a tangible, real-world impact. But tech misuse not only has a tangible real-world impact, it often has devastating consequences, including the economic, emotional, and physical wellbeing of victims and their children. Survivors of tech-facilitated abuse become caught in the crosshairs of an abusive person using tech to mystify and confuse them, skirting the rules of online platforms and leaving support systems more likely to dismiss the behavior.

This threat model is different than what is typically defined as abuse, because it’s not perpetrated by a stranger or a nation state. The abuse often starts in the context of a happy relationship with a sense of excitement and magic. It begins with the feeling that makes us want to share our most intimate selves, and to be seen and held by another. Abusers tell their victims that they are safe with them, and that they can be trusted. Cultural messaging that says in love, there’s no privacy or secrets. Both lead to sharing — passwords, favorite foods, colors, songs, a second-grade teacher’s name, a first pet’s name. All of these things, however, can be used as an answer to a security question designed to protect accounts from malicious access. This is why intimate partner abuse needs to be understood and considered as a very unique and specific threat model when looking at technology and policy design.

We’re told that the more we share — the more of our private selves we give up — the more we demonstrate we are trustworthy. By the same token, the more information we hold back, the more privacy we desire, the less trustworthy we are or may seem. Cultural norms imply there should be minimal to no individual privacy within a relationship, and that we waive our right to privacy when we’re on the road to partnership.

This threat model is like no other, because in many cases the threats are not obvious until it’s too late. Other threat models assume a level of privacy and control over devices and accounts that can keep strangers out. But with intimate partner abuse, there is already physical access to information and devices. This leads to the same sort of victim blaming that happens to survivors of sexual assault when they’re told they shouldn’t have worn certain clothes. It’s not uncommon for victims of technology abuse to hear that they should get offline or give up their phone if they don’t want to be harmed. But the solution simply cannot be for survivors to disengage. Survivors have a right to use technology, to participate in life both online and off, and to live a life free of harassment, abuse, and stalking.

Supporting Victims of Technological Violence

In a relationship where one person has become abusive, key aspects of the victim’s life including friends, family, financial resources, and a safe home, have often been systematically stripped away by the abuser. Technology has revolutionized victim safety and connection. It’s offered a way for some of our society’s most isolated individuals to connect to outside support. It serves as a lifeline, both when they’re in danger and when they’re working to rebuild their life. And it creates a digital trail that can be incredibly helpful in their efforts to hold their perpetrators accountable.

Limiting a victim’s access to technology will NOT stop the abuse they’re experiencing. Technology-facilitated abuse is just an extension of other forms of abuse and usually occurs along with other tactics. Technology is just one of many tools abusers use to harass, threaten, stalk, and harm. Just as we would consider it preposterous to tell a survivor who’s being followed while they drive in their car to get rid of their car, we should realize it is preposterous to say victims should get rid of their technology or go offline when someone is using technology to harm them. Such advice only empowers the abusive partner because it ends up disconnecting the survivor from their community and support systems and cuts off access to vital tools.

We work to support the efforts of technology companies to consider and test against the intimate partner technology violence threat model as they develop products and services. We’re working on helping them build technologies that have processes built in to help those being victimized learn what they can do to reclaim their safety and privacy. We encourage developers, engineers, and public interest technologists to consider a world where not only privacy-by-design, but also safety-by-design, is the default. You are the people who can help detect threats, who can build the critical tools that help survivors connect to the world around them, and can shape those tools in a way that offers them a chance to get out from under the real-world devastation this abuse creates.

*Names and certain details have been changed to ensure privacy.

Corbin Streett brings over 10 years of experience working at the intersection of technology and domestic violence, currently working as a subject matter expert and strategist with the National Network to End Domestic Violence. Providing training and technical assistance to victim advocates, industry experts, and others across the nation, Corbin works to ensure audiences understand the important role technology plays in the lives of survivors, and how to help them stay safely and privately connected.